The New Tariff War Just Crushed Oil Prices — Will It Kill US Shale?

In April 2025, the United States implemented sweeping “reciprocal” tariffs on its major trading partners, imposing new import duties on all energy-related goods – including crude oil, refined petroleum products, liquefied natural gas (LNG), and even oilfield equipment and technology inputs. These tariffs range from a baseline 10% on most imports to much steeper rates (up to 104% on Chinese goods). U.S. trading partners have retaliated in kind, levying tariffs on American energy exports like crude oil and LNG. This report provides a detailed macroeconomic analysis of these policies, using supply and demand frameworks to interpret their impact. We examine:

Short-term (6–12 month) vs. long-term (multi-year) effects on global and U.S. energy prices,

Impacts on U.S. upstream oil & gas activity (capital investment, drilling rates, service costs),

Consequences for smaller U.S. oil producers and how they should prepare,

Why U.S.-based operations might gain advantages while global enterprises and foreign suppliers are disadvantaged, and

Effects on the U.S. dollar and broader macroeconomic indicators.

Our analysis is supported by recent data and insights from credible sources (EIA, IEA, IMF, financial analysts), with graphical supply-demand interpretations to illustrate key concepts.

Short-Term Impacts on Global and U.S. Energy Prices (6–12 Months)

In the immediate aftermath of the tariff announcements, energy markets have experienced sharp price declines and volatility. Fears of an escalating trade war have triggered a negative demand shock for oil and gas, as traders anticipate slower economic growth and hence lower energy consumption.

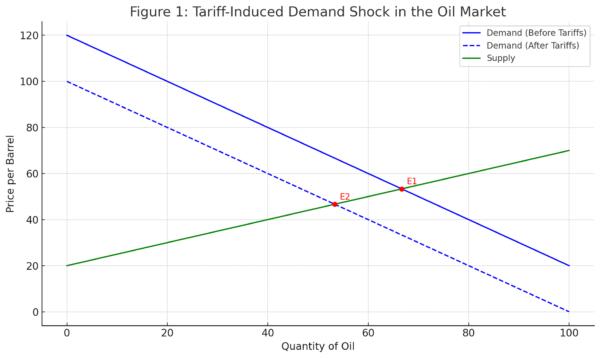

A classic demand and supply graph showing how reciprocal tariffs act as a negative demand shock, lowering the equilibrium price and quantity in the oil market.

Figure 1: Tariffs act as a negative demand shock to the global oil market. An abrupt drop in expected demand (from D1 to D2) shifts the demand curve leftward, causing the equilibrium price to fall (from P1 to P2) along a relatively fixed short-run supply curve (S). The result is a lower price and reduced quantity (Q1 to Q2). This theoretical graph explains why crude prices plunged when tariff news hit – markets are pricing in weaker demand growth due to trade tensions. In the short run, supply cannot adjust quickly, so prices must decline significantly to restore market balance.

In practical terms, crude oil prices have indeed fallen sharply since the tariff announcement. Within days, both global Brent and U.S. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) benchmarks dropped to their lowest levels in years. For example, by April 8, 2025, WTI had sunk to about $59.58 per barrel and Brent to $62.82, roughly 16% below their levels before the tariff news. Oil markets had “slumped by 16%” in less than a week after President Trump’s April 2 tariff announcement. This rout erased months of price gains, bringing oil to levels not seen since the 2020–21 pandemic era. Analysts note that the sudden shift in economic outlook – from expected modest growth to rising recession fears – is driving the selloff in crude. In effect, the tariffs have introduced a shock of uncertainty, causing investors to anticipate weaker demand and thus lower prices.

Several short-term factors are at play:

Global Demand Fears: The tariffs sparked concerns of a global slowdown or recession. China – the world’s largest crude importer – retaliated with its own tariffs, further rattling markets. As one analyst explained, “The scenario has presented a case for a global recession, where fears of energy demand declining have emerged”. The International Energy Agency (IEA) has trimmed its oil demand growth forecasts due to “deteriorated” macroeconomic conditions amid escalating trade tensions. In its March 2025 report, the IEA projected global oil demand growth at just ~1.03 million barrels/day, revising down earlier estimates and now seeing a 600,000 bpd surplus of supply in 2025. Such oversupply expectations put immediate downward pressure on prices.

Market Sentiment and Financial Flows: Equities and commodities sold off in tandem. Oil is a risk-sensitive asset, and the punishing worldwide sell-off in stock markets spilled into the oil market as well. The S&P 500 Energy Index fell over 15% in the days after the tariffs, reflecting pessimism about the sector. As investors flocked to safer assets, petroleum futures faced a wave of liquidation, accelerating price declines. There is a clear sense of “demand destruction” being priced in as the trade war escalates.

Initial Resilience & Volatility: Notably, oil prices initially rallied when tariffs were merely threatened but reversed course violently once they took effect. On April 2, WTI and Brent rose about 0.6–0.7% early in the day (with WTI settling at $71.71), only to flip into negative territory during President Trump’s press conference that afternoon. The intraday reversal – a swing of over $1/bbl – underscored how uncertainty and shifting policy signals are whipsawing the market. By week’s end, oil was set for its worst week in months.

Tariffs on Energy Commodities: The reciprocal tariffs directly increase the cost of some cross-border energy flows, although immediate physical impacts are limited in the short term. The U.S. notably spared Canada and Mexico’s crude exports under USMCA agreements, recognizing the dependence of U.S. refiners on North American oil. However, China’s retaliation did hit U.S. energy exports, including a 10% import tariff on U.S. crude oil and 15% on U.S. LNG. Given that U.S. crude made up only ~5% of China’s imports, Chinese buyers can relatively easily replace or reroute these barrels, but it added to negative market sentiment. In the LNG market, the Chinese tariff on U.S. LNG cargoes likewise pushed those volumes toward other Asian or European buyers, slightly depressing spot LNG prices in the short term due to re-routing inefficiencies. (China had previously become the world’s top LNG importer; a 15% cost penalty on U.S. LNG makes those cargoes less competitive, at least temporarily.)

Refined Products and Other Fuels: Tariff impacts on refined petroleum products are also emerging. If U.S. imports of fuels (like gasoline or diesel from Europe or neighbors) face new tariffs, domestic U.S. fuel prices could see localized upticks relative to crude. Conversely, any foreign tariffs on U.S. refined exports will divert those flows elsewhere. For now, most partners’ tariff responses have targeted broader goods categories, but energy-specific friction is evident. China, for instance, did not exempt U.S. coal (15% tariff applied) or crude, but interestingly excluded U.S. LPG and ethane from retaliation, since China relies on these for petrochemical feedstock. This selective approach indicates that in the short run, countries are calibrating tariffs to hit back at U.S. energy exports where alternatives exist, while avoiding products where they are highly import-dependent.

Bottom-line (Short-Term): The immediate effect of the reciprocal tariffs has been lower global energy prices, driven by a demand-side shock and worsened market sentiment. In the next 6–12 months, analysts widely expect oil prices to remain under pressure. For example, Goldman Sachs now forecasts Brent at around $62 and WTI around $58 by the end of 2025 under the tariff scenario – a markedly subdued outlook. Some forecasts even see WTI slipping into the mid-$50s if the trade war deepens into stagflation. Natural gas prices in the U.S. may stay soft as well; record U.S. gas production and limited LNG export growth (due to tariffs and weaker global demand) could lead to an oversupplied domestic market in the short term. Overall, energy consumers benefit from temporarily lower prices at the expense of producer revenues. But as we discuss next, these short-term gains for consumers come with longer-term risks to supply and market stability.

Long-Term Impacts on Energy Prices and Markets (Multi-Year)

Looking beyond the immediate horizon, the reciprocal tariffs could reconfigure energy markets and price dynamics in lasting ways. The long-term impacts (over several years) will depend on how producers, consumers, and policymakers adapt. Key long-range considerations include:

Reduced Investment and Supply Growth Constraints: Prolonged trade uncertainty and low prices will likely curtail capital spending in the oil and gas sector globally. The United States – which has been the largest source of new oil supply – is expected to slow its output growth. The IEA projects that U.S. production will still rise, but more slowly, contributing to an ample supply surplus of ~600,000 barrels/day in 2025. If tariffs and low prices persist, companies could cancel or delay projects, leading to underinvestment in new supply capacity. This sets the stage for tighter supply down the road. In the long run, supply curves will shift left (upward) as high-cost producers exit and drilling activity diminishes, partially offsetting the demand weakness. After an initial glut, the market could tighten in later years if demand recovers but supply growth has been choked off by years of low investment. This dynamic implies that the ultra-low prices seen in the tariff shock may not be permanent – a partial rebound is possible in the outer years as the market rebalances. For instance, Goldman’s scenario sees WTI recovering slightly to ~$51 by late 2026 (from high-$50s in 2025) as the supply overhang eases.

Demand Destruction vs. Structural Changes: A multi-year trade war might shave off a portion of long-term global demand for fossil fuels. Higher import costs and slower economic growth in multiple countries could lead to demand destruction – e.g. industries becoming more energy-efficient or switching to non-tariffed energy sources. The IMF warns that the tariffs pose a “significant risk to the global outlook”, and if global GDP grows more slowly, oil demand growth will likewise be weaker each year. The IEA already factored in “escalated trade tensions” to cut its 2025 oil demand estimate by 70,000 bpd. While that figure is modest, a protracted tariff regime could compound over time. We may see a permanent demand loss for oil on the order of a few hundred thousand barrels per day if world trade volumes and industrial output settle at a lower trend. On the other hand, some demand could merely be deferred – if tariffs eventually ease, there might be a rebound in economic activity and oil consumption.

Price Stabilization and OPEC+ Response: In the long-term, global actors like OPEC+ are likely to adjust to the new environment. Facing a potential multi-year surplus, OPEC and its allies might restrain output more aggressively to prop up prices. Already in early 2025, OPEC+ began unwinding some production cuts, but the tariff-driven demand outlook may force them to reconsider and possibly re-cut production. If the tariff war drags on, OPEC+ could become more active in managing supply to prevent prices from collapsing – effectively putting a floor under oil prices in the long run (albeit at a lower level than pre-tariff expectations). Thus, after the initial free-fall, one could expect oil prices to eventually find a new equilibrium. Many analysts see this equilibrium in the $50–$70 per barrel range over the next few years, as opposed to the $70–$90 range that might have prevailed without the trade conflict. Notably, the U.S. administration itself has signaled it is comfortable with (even desirous of) lower oil prices around $50 to achieve energy cost relief – meaning policy pressure (through tariffs, strategic reserves, etc.) might continue to cap prices.

Changes in Trade Flows and Differentials: In a prolonged tariff scenario, global energy trade routes will reorient. Countries will seek tariff-free alternatives: for instance, China may permanently reduce U.S. oil and LNG purchases, cementing relationships with Middle Eastern, Russian, or African suppliers. U.S. exports might pivot more towards allies with no tariffs (e.g. more U.S. LNG to Europe, more crude to South Korea or India if bilateral deals are struck). This could affect regional price differentials. U.S. crude (WTI) might trade at a bigger discount to Brent if Asian demand for U.S. barrels stays constrained by tariffs, leading to a domestic glut. Similarly, U.S. natural gas (Henry Hub) could remain relatively cheap if LNG export growth to Asia is stunted, benefiting U.S. industrial consumers long-term. Conversely, tariffs on imports into the U.S. (if they persist on certain refined products or equipment) might create slight domestic price premiums for those commodities due to added import costs. Overall, while the world price of oil is set globally, tariffs can introduce wedges – e.g., delivered price of U.S. crude into China stays higher than Brent, discouraging that route. Over multiple years, such distortions can become entrenched, effectively fragmenting what was previously a more unified global energy market.

In summary, the multi-year outlook under a tariff regime is for an initially oversupplied, low-price environment to gradually give way to a more balanced market at somewhat lower-than-pre-trade-war price levels. Consumers globally might enjoy a period of cheaper energy, but at the cost of market instability and potential future supply tightness if investment is too depressed. Policymakers (OPEC+, etc.) will likely intervene to prevent a complete price collapse. Thus, while short-term prices are sharply down, longer-term prices could stabilize at a moderate level – unless the trade war escalates into a true global recession (which would further suppress demand and keep prices low longer). Notably, major forecasters like the IEA and EIA still predict some demand growth in coming years (driven by emerging Asia), so a gradual recovery in oil prices from today’s trough is anticipated, albeit to a lower plateau.

Effects on U.S. Upstream Oil & Gas Activity (Investment, Drilling & Costs)

The tariff shock is reverberating through the U.S. upstream oil and gas industry. In the short run, oilfield activity is expected to pull back, and in the longer run the industry must adapt to higher costs and price uncertainty. Several facets are worth examining:

- 1. Capital Investment and Drilling Rates: U.S. exploration and production (E&P) companies are tightening their budgets in response to lower prices and uncertain policy. Coming into 2025, many shale producers had already adopted capital discipline, and the tariffs reinforce that cautious stance. According to industry surveys, producers planned to reduce 2025 capital expenditures by a few percent from 2024 levels. With WTI now languishing in the low $60s or below, drilling programs are being re-evaluated. If WTI remains in a ~$55–$60 range for a sustained period, a noticeable decline in U.S. shale drilling activity is likely by the second half of 2025. Rystad Energy notes that a sub-$60 price deck could lead to rig count drops as marginal wells become uneconomic.

Early data already show a potential inflection: Baker Hughes rig counts, which had been roughly flat in early 2025 (~590 rigs active), may start falling as companies delay drilling new wells. Smaller independent drillers, in particular, are likely to freeze new projects and focus only on their best prospects. Big oil companies (the majors) might also defer some expensive ventures (like frontier deepwater or exploration) until there’s more certainty. Overall upstream capital investment for 2025 is now projected to grow only marginally (if at all), a downgrade from earlier expectations of growth – Deloitte, for instance, cut its outlook to only ~0.5% capex increase for the year, citing tariff-related caution. The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas quarterly energy survey captures the sentiment: most executives reported they will decrease capital spending and “lower activity in the shale patch” due to the 25% steel import tariffs and related trade policies.

In effect, the tariffs have created a double hit for upstream firms: lower revenue per barrel and higher costs per well. This combination threatens profit margins, so companies are scaling back. One anonymous shale executive lamented that “Drill, baby, drill is nothing short of a myth… Tariff policy … doesn’t have a clear goal. We want more stability.” – highlighting how the uncertain policy environment is causing firms to hesitate on long-term investments.

- Oilfield Service Costs and Supply Chain: A crucial impact of the tariffs is the rise in costs for oilfield equipment, materials, and services. The U.S. upstream sector relies on a global supply chain for parts like steel tubing, valves, drilling rigs, and specialty chemicals. The new tariffs – especially the 25% tariffs on imported steel and other industrial inputs – have made these inputs more expensive. Oilfield service companies confirm that “Pipes, valve fittings, sucker rods are going to be impacted by tariffs”, according to Rystad Energy. Many U.S. oilfield service firms source equipment or components internationally, so they face higher input costs and potential delays. Morningstar estimates that the tariff-driven cost inflation will shave 2–3% off oilfield services revenue in 2025, and even more off operating profit (given reduced efficiency). In fact, for each $1 lost in revenue, $1.25–$1.35 of operating profit could evaporate for major service companies due to lost scale and higher costs. This profit squeeze has already hit the market capitalization of oilfield giants: shares of SLB (formerly Schlumberger), Halliburton, and Baker Hughes all tumbled 10–12% in early April on the tariff news.

From the producers’ perspective, the cost of drilling and completing a well has climbed. Steel casing and tubing are estimated about 30% more expensive than before the tariffs, significantly raising well costs. As a result, the breakeven oil price needed for new drilling has ticked upward. The Dallas Fed survey found the average WTI price needed to profitably drill a new well rose to $65/bbl, up from $64 last year – a small increase, but telling in a tight-margin business. Some executives even say “$70 per barrel is the new $50” in terms of what price is needed to justify aggressive drilling. This echoes the analysis by industry researchers: IEEFA notes that rising drilling costs (partly due to tariffs) have moved the U.S. oil cost curve up, so companies are squeezed between low prices and higher expenses. In practical terms, higher steel and equipment costs mean fewer wells get drilled for the same budget, slowing production growth.

Service Rates: With drilling activity poised to slow, oilfield service providers (rig contractors, fracturing crews, etc.) may actually face an oversupply of equipment, which could paradoxically cap service price inflation. However, any hardware or parts that must be imported will carry the tariff premium. Thus, we expect service margins to compress (companies eat some of the cost) even if service prices to producers rise modestly (producers pay more per job). Producers might also try to substitute toward domestic suppliers for equipment to avoid tariffs, supporting local manufacturing of oilfield components. Over time, this could benefit U.S. equipment makers (e.g. domestic steel mills, tool manufacturers) if they scale up to fill the gap – a stated goal of the administration’s policy (to “reindustrialize the country” and use more American-made inputs). In the interim, though, bottlenecks could occur for certain specialized items not easily sourced domestically, potentially causing project delays.

Upstream Outlook: In the coming 1–2 years, U.S. oil output growth will likely slow, though not necessarily decline outright. The U.S. entered 2025 at record production levels, so even a slowdown still means a high baseline of output. Large companies will continue operating their most efficient rigs and completing drilled-but-uncompleted (DUC) wells to maintain output. But the era of explosive shale growth could be tempered. If prices stay around $60 or lower, smaller operators will scale down, high-cost fringe plays (like some fringe shale basins or deepwater projects) might be shelved, and consolidation could accelerate (as weaker players sell assets to better-capitalized firms).

On the cost side, service cost inflation may eventually be tamed if demand for services falls enough – a sort of self-correcting mechanism. In 2015–2016, for example, a drilling downturn led service companies to sharply discount to keep business. A similar pattern may occur in 2025: after an initial spike in steel prices from tariffs, the overall upstream cost index could flatten or even decline if activity drops and suppliers compete for fewer jobs. Indeed, prior to the tariff announcement, analysts expected flat oilfield costs for 2025; now cost forecasts are being revised slightly upward, but not sky-high, due to likely reduced demand for services.

In summary, U.S. upstream firms are bracing for a challenging environment of lower prices, higher costs, and policy volatility. The near-term effect is a probable dip in drilling rates and cautious capital spending. Longer-term, the industry may adjust by focusing on efficiency and domestically sourced inputs, which could eventually mitigate some cost pressures. But until then, upstream profit margins will be under stress. As one industry observer put it, tariffs are “provoking cost increases in materials and equipment … while causing economic jitters that depress demand”– a painful combination for the oil patch.

Outlook for Smaller U.S. Oil Producers (Independents)

Smaller independent oil producers – often highly leveraged and operating narrower-margin projects – face particularly tough consequences from the tariff-driven market changes. These companies must prepare for a more hostile business environment relative to the pre-tariff status quo. Key challenges and recommended preparations for smaller producers include:

Cash Flow Squeeze: With WTI oil prices now hovering around or below the breakeven levels for many independents, smaller firms will see thinner cash flows. A Dallas Fed survey noted many shale operators need about $65 per barrel to drill profitably, yet futures are now in the low $60s or below. This means some planned wells are no longer cash-flow-positive. Smaller producers, who typically don’t have downstream or diversified income, will likely scale back drilling to live within cash flow. They should prepare for lower revenues by reducing operating costs (renegotiating service contracts, optimizing field operations) and improving efficiencyper well. Those who hedged a portion of their 2025 production at higher prices will be partially shielded; others may need to consider hedging future production on price upticks to lock in survival prices.

Rising Input Costs & Capital Constraints: Unlike majors, small firms have less bargaining power to absorb higher costs for steel, equipment, and services. The ~25% tariff on imported steel translates into notably higher expenses for drilling pipe, casing, production tubing, tanks, etc. Independents will feel these cost increases immediately on new projects. Furthermore, financial conditions are tightening – lenders and investors, worried about tariff uncertainty and low prices, may be less willing to extend credit. This limited access to capital means small E&Ps must be prepared to self-fund out of pocket or seek consolidations. We may see an uptick in asset sales or mergers as weaker players cannot afford to continue alone. Preparation: Smaller operators should shore up their balance sheets – build cash reserves during any price rallies, pay down debt, and avoid costly new commitments. Those with strong balance sheets will be better positioned to ride out the turbulence or even acquire distressed assets at a discount.

Hedging Policy and Risk Management: The volatility introduced by trade policy means price swings could be sudden and deep (as witnessed by the recent $10+/bbl drop). Small producers should strengthen their risk management, e.g. by hedging a portion of production with swaps or options to ensure they can cover operating costs even if prices crash further. They should also factor in potential basis risk – if U.S. crude trades at a bigger discount due to export barriers, local prices might underperform global benchmarks. Using Gulf Coast pricing or basis hedges might be prudent for those exporting or selling into coastal markets.

Operational Agility: Lean operations will be crucial. During prior downturns, nimble independents survived by rapidly cutting non-essential expenditures and high-grading their drilling inventory (focusing only on the most productive acreage). Smaller producers should have contingency plans to idle rigs quickly, lay down crews if needed, and concentrate on maximizing output from existing wells (through workovers, artificial lift, etc., which may yield better returns than drilling new wells in a low-price environment). Additionally, they can explore cost-sharing measures like joint ventures to spread the financial risk of drilling new wells.

Policy Navigation: Finally, small producers should stay attuned to policy developments. The trade environment is fluid – there is a chance tariffs could be rolled back if negotiations progress, or alternatively, new tariffs (or non-tariff barriers) could emerge on other inputs. Engaging with industry groups and regulators to voice their concerns (for example, highlighting how steel tariffs hurt domestic energy growth) is advisable. They may also seek any government relief measures that become available (such as temporary waivers or subsidies for U.S.-made equipment).

In essence, smaller oil companies need to go into survival mode. The current situation resembles previous industry downturns where only the lowest-cost and best-capitalized survive. By cutting costs, hedging bets, and possibly restructuring operations, independent producers can increase their odds of weathering the tariff storm. Those that do survive might emerge into a market with fewer competitors (if some peers go bankrupt), potentially allowing them to thrive when conditions improve. Nonetheless, preparation for a sustained period of low prices and high uncertaintyis key. As one industry insider with 40+ years experience noted, “I have never felt more uncertainty about our business… Tariff policy is injecting uncertainty into the supply chain”– a sentiment that encapsulates the need for vigilance among the smallest players.

U.S.-Based Operations vs. Global Enterprises: Who Wins and Who Loses

The tariff policy is explicitly designed to favor domestic U.S. production and penalize foreign goods – and this dynamic creates relative winners and losers in the energy sector:

Advantages for U.S.-Based Operations: Companies that produce or manufacture within the United States stand to gain relative advantages. For example, a U.S. refinery running domestic crude oil will not face import tariffs on that feedstock, whereas a competitor reliant on imported crude might (if those imports are from tariffed countries). The U.S. government’s aim is to encourage allies and trading partners to buy “growing American exports” in energy – and indeed, some partners are reacting by negotiating increased purchases of U.S. energy. (Trump cited potential deals for large-scale purchases of U.S. LNG by countries like South Korea.) If such deals materialize, U.S. gas producers and LNG exporters could gain guaranteed market share despite the trade turmoil. Domestically, U.S. oil producers benefit from tariffs on foreign oil to the extent those tariffs raise the cost of imported crude or fuels, making U.S.-produced oil relatively more competitive in the home market. It’s worth noting that Canada and Mexico (the top two sources of U.S. oil imports) were largely exempted from direct oil tariffs in this round. However, if tariffs ever applied broadly to imported crude, U.S. producers would effectively see a tariff shelterfor a portion of domestic market share.

Additionally, U.S. equipment manufacturers and service providers could capture business that previously went to foreign suppliers. For instance, if a drilling rig or critical component was typically imported from Europe or China, a U.S. supplier might now have the price edge to win that sale. Over time, this could stimulate domestic manufacturing of oilfield equipment, aligning with the “reindustrialization” goal. U.S. steel mills, for example, benefit from a 25% tariff on imported steel, which gives them room to raise prices and volume domestically (assuming demand holds up).

There is also a geopolitical benefit for U.S. energy operations: By making foreign energy more expensive, trading partners might increase their dependence on U.S. energy exports to avoid punitive tariffs. The administration has explicitly linked trade deals with energy purchases – e.g. Europe was told tariffs could be avoided if they “zero out” their tariffs and “buy our energy”. Such pressure could secure long-term contracts for U.S. LNG or oil. In summary, U.S.-centered energy value chains (from upstream production to midstream transport to downstream refining within the U.S.) are positioned to gain volume and share domestically, even if total global trade shrinks.

Disadvantages for Global Enterprises and International Suppliers: Globally diversified energy companies and foreign suppliers are bearing the brunt of the tariff disruption. Multinational oil companies that rely on cross-border supply chains face higher costs and complexity. For example, a global oilfield services firm that manufactures equipment in Asia for use in Texas now has to pay tariffs on those imports, eroding its profit. Companies like Halliburton, Schlumberger (SLB), and Baker Hughes have already seen their valuations cut by 3–6% in light of the expected hit from tariffs. These firms operate worldwide, so trade barriers increase their operating friction. Global traders and majors that move crude and products around are also hit – tariffs on flows mean some trades are no longer economical, reducing trading profits and arbitrage opportunities.

Foreign energy exporters to the U.S. are clear losers. Although Canada and Mexico escaped the immediate crude tariffs, other countries face steep duties. For instance, any OPEC country or Brazil exporting oil to the U.S. now encounters the baseline 10% tariff (or more if categorized as a “tariff-abusive” nation). This disadvantages their oil versus U.S. oil in the American market. They may have to divert shipments elsewhere, potentially at lower netbacks. Similarly, foreign refiners who ship fuels into the U.S. (e.g. European gasoline exporters to the East Coast) could lose out if their products become tariff-laden and thus costlier than fuel made in U.S. refineries. On the LNG front, countries like Qatar or Australia exporting LNG to the U.S. (which is minimal) aren’t a factor, but more relevant is international competition in third markets: U.S. LNG now faces Chinese tariffs, so international LNG suppliers (like Qatar, Russia) gain an edge in China, while U.S. LNG might deepen in tariff-free markets.

In short, the playing field tilts in favor of domestic players. A concrete example: A U.S. small oilfield manufacturer of valves saw its larger Chinese competitor’s products suddenly double in price due to a 100%+ tariff; this allows the U.S. firm to win contracts it previously couldn’t – a boon for the U.S. business, but a loss for the Chinese firm. On a bigger scale, global enterprises that thrived on free trade – moving rigs, crews, oil, and capital freely – now must navigate a fragmented system. Many are incurring immediate losses (stock market declines reflect this), and over the long term they might shift strategies (for instance, relocating some manufacturing to the U.S. to avoid tariffs, or focusing on tariff-free trade lanes).

It’s important to note that “advantage” in this context is relative. U.S. operations are still seeing lower prices and some cost inflation, just less severely than their foreign counterparts who face both the market downturn and lost market access. For example, U.S. Gulf Coast refiners benefit from discounted domestic crude, but some of them also lost an export outlet (e.g. gasoline exports to Mexico could face retaliation). So even domestic winners have some offsetting challenges. Meanwhile, a global company like ExxonMobil or Chevron with operations everywhere experiences both sides: their U.S. upstream might gain from a domestic focus, but their international projects and sales suffer. This may encourage such companies to pivot investment back to U.S. projects (like Chevron focusing on Permian Basin where it now plans to “triple-frac” wells to cut costs) because the U.S. market appears slightly more protected.

Net effect: The tariff regime furthers the trend of localizing energy supply chains. Domestic U.S. energy businesses (upstream, midstream, downstream, manufacturing) have a home-field advantage and could capture greater share of domestic demand and even certain export deals brokered politically. International firms and exporters, lacking that shelter, will likely lose market share in the U.S. and face more competition elsewhere. Over time this could reduce global efficiency (as comparative advantage is distorted), but it aligns with the policy goal of U.S. “energy dominance” and re-shored industrial activity. Energy companies will adjust by restructuring supply lines (e.g. sourcing materials within tariff-free zones) and lobbying for exemptions, but many global enterprises will find the next few years challenging and less profitable due to these tariffs.

Impact on the U.S. Dollar and Broader Macroeconomic Indicators

Beyond the energy sector, the reciprocal tariffs are influencing currency values and key macroeconomic metrics for the U.S. and global economy. Here we analyze the impact on the U.S. dollar and indicators such as inflation, GDP growth, trade balances, and interest rates:

U.S. Dollar (USD): The immediate aftermath of the tariff escalation saw an unusual reaction in currency markets – the typically “safe-haven” U.S. dollar weakened as global investors grew skittish about U.S. assets. In early April, as stocks plunged, “the U.S. dollar crumbled” and fell broadly against other major currencies. Investors fled to alternatives like gold and the Swiss franc, sending the dollar down about 0.5–1% versus major currencies (e.g. USD dropped to ¥145, a 0.9% slide, and to 0.843 CHF). This is somewhat counterintuitive – often, in times of global turmoil, the dollar strengthens. However, in this case, the turmoil’s epicenter is the United States’ own trade policy, causing concern that U.S. economic prospects are deteriorating and that the Federal Reserve might cut interest rates in response. Indeed, U.S. treasury bonds sold off heavily (prices down, yields up) on fears of higher inflation and risk, making dollar assets less attractive.

Over the medium term, currency experts suggest tariffs can put upward pressure on the dollar through trade mechanics (tariffs reduce U.S. import demand, which can improve the trade balance and support the currency). But the volatile nature of this trade war regime may dampen the typical currency effect. If global investors continue to perceive the U.S. as instigating risky economic conflict, they may diversify away from the dollar, especially if other countries retaliate by coordinating financial measures. So far, the evidence points to a more fragile USD. The dollar’s trajectory will depend on how the macro story unfolds: a significant U.S. slowdown and Fed easing would likely weaken the dollar further, whereas if tariffs merely shift trade flows but the U.S. avoids recession, the dollar could regain strength.

For energy markets, a weaker dollar can actually be bullish for oil prices (since oil is priced in USD, a weaker dollar boosts non-U.S. purchasing power). However, in this scenario, the demand destruction effect seems to be outweighing any currency effect on oil. If the dollar does continue to drop, it might cushion oil’s fall somewhat in global terms. Conversely, should the dollar rebound (e.g. if Europe or others suffer more), that could put additional downward pressure on commodity prices. In summary, the USD is caught between traditional safe-haven flows and the unique self-inflicted nature of these tariffs – leading to uncharacteristic volatility. At least initially, the tariff shock has been USD-negative in markets.

Inflation and Consumer Prices: Import tariffs are essentially a tax on goods coming into the country, so they raise costs for businesses and consumers. The breadth of these tariffs – effectively a baseline 10% on all imports plus higher rates on key partners – means many consumer products (from electronics to apparel) will get more expensive. Energy tariffs specifically could raise costs for certain fuels or equipment. Economists warn that the tariffs “could reignite inflation” in the U.S.. Early estimates suggest the cumulative tariffs in 2025 might raise the U.S. price level by about 2–3% in the short run, equivalent to an extra burden of several thousand dollars per household. Reuters reported that on average, tariffs could “boost costs for the average U.S. family by thousands of dollars” per year. This is a significant hit to consumer purchasing power and effectively a tax increase. In energy, Americans might see somewhat higher gasoline prices at the pump this summer than they otherwise would, because refiners could pass on some costs of tariffed components or crude (though the drop in global oil prices offsets this to a degree). If, hypothetically, tariffs had hit Canadian or Mexican oil, U.S. gasoline prices would spike due to constrained supply – luckily that was avoided for now. Still, fuel prices may not fall as much as crude prices have, because other inputs (ethanol imports, additives, etc.) might be tariffed and add cost.

Rising inflation is a problem because it could prompt the Federal Reserve to consider interest rate hikes at the wrong time – when the economy is weakening. This confluence (higher inflation, slowing growth) is the dreaded stagflationscenario. The IEA even referred to a “tariff-induced stagflationary scenario” clouding the oil demand outlook. The IMF’s chief also highlighted this risk, urging avoidance of steps that harm the world economy. Currently, core inflation rates have ticked up due to import duties, and businesses are reporting higher input costs in surveys.

Economic Growth and Recession Risk: The tariffs act as a drag on economic growth in multiple ways. They disrupt supply chains, create inefficiencies, and invite retaliatory hits to U.S. exports. Both the IMF and private banks have slashed U.S. growth forecasts for 2025 in response. J.P. Morgan now sees a 60% chance of a U.S. (and global) recession by year-end 2025, up from 40% before. Some analysts are even more pessimistic: one forecast cited by Fortune expects U.S. GDP to actually contract slightly in late 2025 if all tariffs stick. Essentially, what was a late-cycle mild expansion could turn into a downturn due to self-inflicted trade wounds.

On the global stage, the IMF estimated that a universal 10% increase in tariffs by the U.S. (with retaliation) could cut U.S. GDP by ~1% and global GDP by ~0.5%. We are now seeing tariffs well above 10% for some trade lanes, so the impact could be on that order or greater. Early evidence of slowdown is emerging: business confidence indices have fallen, and manufacturing orders are down as companies postpone decisions until they gauge the tariff impacts. In energy terms, a recession would further suppress oil and gas demand, reinforcing the low price environment.

Trade Balances: Paradoxically, while tariffs are meant to reduce trade deficits (President Trump cited the $350 billion EU deficit and said “it’s gonna disappear fast”), the outcome may not be so straightforward. U.S. imports will likely decrease because of higher costs, but U.S. exports are also facing barriers abroad. For energy, one possible outcome is a reduced volume of U.S. energy exports in the near term (e.g. fewer LNG cargoes to China, less oil to certain destinations) which could temporarily increase domestic inventories. On the other hand, if allies agree to buy more U.S. energy to placate trade issues (as hinted with South Korea LNG, or potentially Europe oil purchases), then U.S. exports could hold up or even rise in some areas. Net-net, the U.S. trade deficit in energy might actually improve because the U.S. is a net exporter of petroleum now and an exporter of LNG – if imports fall and exports only slightly drop, the net balance improves. But the overall trade deficit could worsen if retaliation hits other sectors (like aircraft, agriculture) where the U.S. loses export revenue. Moreover, any gains from tariffs (tariff revenue to the government) may be offset by lower export incomes for U.S. companies and farmers, making the current account impact ambiguous.

Financial Markets and Investment: The tariffs have clearly spooked financial markets. Stocks saw a “global meltdown” with U.S. indices down ~4-6% in one day, and credit spreads widening as investors fear corporate profit hits. If this persists, it can create a negative wealth effect (households feeling poorer, cutting spending) and raise the cost of capital for businesses (as their stock and bond prices fall). Already, interest rate-sensitive sectors (like housing, autos) are nervous that inflation from tariffs will lead to higher interest rates despite a slowing economy. The Fed’s stance will be critical: do they fight inflation (raise rates) or support growth (cut rates)? The worst-case would be stagflation where they have no good options.

From a macro-policy standpoint, some fiscal breathing room exists: the tariff revenues (some estimates say up to $3.1 trillion over 10 years if all tariffs remain) could theoretically be redistributed or used to aid affected industries. However, such revenues also come out of consumers’ pockets in effect. Meanwhile, if a recession looms, we might see stimulus measures or a backing off of tariffs due to political pressure (especially ahead of elections). So macro indicators could swing again if policies shift.

Summary (Macro): The reciprocal tariff conflict is acting as a drag on the global economy and is a source of macroeconomic uncertainty. Key indicators to watch:

Inflation: Upward drift (by 1-3 percentage points potentially) – already noted by economists.

GDP growth: Downward revisions – significant risk of recession by end of 2025.

USD: Volatile; initial weakening as investors seek stability elsewhere.

Trade deficit: Possibly lower import bill, but also jeopardized exports; net effect TBD, with high volatility in monthly trade figures likely.

Industrial production: Could dip as supply chain disruptions cause delays and cost increases, offset slightly if some production shifts onshore.

Employment: Certain sectors (steel, possibly domestic manufacturing) may add jobs due to protection, but others (export-oriented manufacturing, farming, and parts of the energy sector) could shed jobs. The oil patch, for instance, might see layoffs if drilling falls off.

The macro picture is one of a trade-off between objectives – trying to boost domestic industry via tariffs is coming at the cost of economic efficiency and stability. As the IMF cautioned, “avoid steps that could further harm the world economy” – a clear sign that the current tariff strategy poses non-trivial systemic risks. Energy is just one piece of this puzzle, but as a globally traded commodity, it’s both affected by and contributes to these macro trends (e.g. cheap oil holds down inflation a bit, but is a symptom of weak demand). In the coming months, policymakers will need to monitor these indicators closely and potentially adjust course if stagflationary signals grow stronger.

Conclusion

The newly implemented reciprocal tariffs on energy goods are reshaping the economic landscape for the U.S. and its trading partners. In the short term, the tariffs have delivered an oil price shock – acting much like a sudden drop in demand in our supply/demand model (Figure 1) – leading to lower global energy prices and immediate strain on the oil & gas industry. U.S. upstream activity is slowing as companies grapple with lower revenue per barrel and higher costs per well. Smaller producers are especially vulnerable and must hunker down to survive, focusing on efficiency and financial resilience.

Over the long term, these trade measures could entrench a new equilibrium in energy markets: one characterized by moderate prices (lower than pre-tariff trends), somewhat lower global demand growth, and potentially slower supply expansion due to reduced investment. U.S. operations may emerge relatively stronger on the global stage – benefiting from protected domestic markets and mandated purchases of U.S. energy by some partners – while international enterprises and exporters face losses and must adapt their strategies.

The macroeconomic ripple effects are significant. Consumers enjoy cheaper oil for now, but face higher prices on many other goods due to tariffs, squeezing real incomes. The U.S. dollar’s behavior has been jolted, and investors are weighing inflation risks against recession risks. Recession odds have risen and the situation remains fluid. Should the tariffs persist, policymakers might need to mitigate the downsides (for instance, through targeted relief to affected industries or a monetary response to support growth). Conversely, a negotiated easing of tariffs would likely boost confidence, lift energy demand expectations, and firm up prices again.

In conclusion, the reciprocal energy tariffs have set in motion a complex chain of economic adjustments. The global energy system is experiencing both the visible price changes and the less visible investment shifts that will shape supply and demand in years to come. Companies – especially in the energy sector – are recalibrating under the new rules of the game. As this report has detailed, the short-term pain is evident in market prices and industry metrics, while the long-term outcome will depend on how quickly actors adjust and whether the policies become a new status quo or a bargaining chip in negotiations. We will continue to monitor data from the U.S. EIA, IEA, IMF and others to update these insights, but for now, stakeholders should brace for a period of heightened uncertainty, with tariff policy becoming a pivotal driver of energy economics rather than just a political sidebar.

Sources:

International Energy Agency (IEA), Oil Market Report March 2025 – demand/supply revisions amid trade tensions.

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) – export/import statistics.

Reuters, Apr 2025 – news on tariffs and market reactions.

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas – Energy Survey 1Q25 (comments on breakevens and tariffs).

IEEFA, Apr 2025 – “Profit squeeze amid shifting landscape” (industry commentary on tariffs, cost pressures).

Argus Media, Apr 9, 2025 – report on tariff implementation and “energy dominance” strategy.

Vortexa Analytics, Feb 2025 – analysis of U.S. tariff threats on crude flows (Canada/Mexico/China impacts).

U.S. IMF statements / Guardian, Apr 2025 – Kristalina Georgieva’s warning on global risks.

Reuters, Apr 3, 2025 – “Tariffs sow fears…$2,300 iPhone” (economic analysis, family cost impact).

Reuters, Apr 8, 2025 – oil price low and recession fears (Goldman and JPMorgan forecasts).

Additional data compiled from JPMorgan, Morningstar, and Deloitte analyses (2025 outlooks).

OPX AI is an engineering services company that helps organizations reduce their carbon footprint and transition to cleaner and more efficient operations.